Clik here to view.

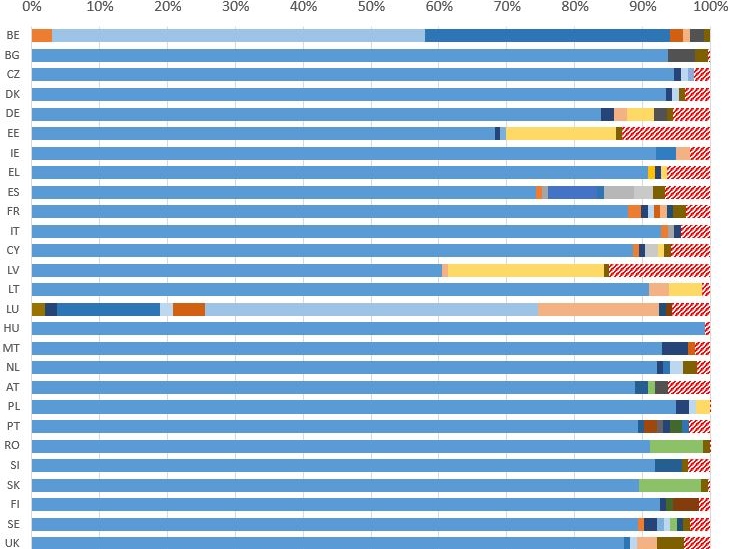

The national language is the mother tongue of the vast majority of citizens in most European states (Source: Josu Amezaga, MQ Lecture, 22-11-2017)

Last week, Professor Josu Amezaga from the University of the Basque Country, Spain, visited Macquarie University to speak about minority languages: what they are and why they should be given space in the ongoing conversation about linguistic diversity.

Participating in this seminar was a timely opportunity as I embark on my PhD journey. I realized that it is one thing to read books and theses arguing about different forms of linguistic inequalities and yet another to engage in an academic debate. Coming from the Philippines, which is home to 187 languages, according to Ethnologue, I went into this seminar hoping to better understand the value – or lack of value – of these belittled languages.

Focusing on European languages, Professor Amezaga traced the historical roots of the monolingual paradigm to the French Revolution. The one-language-one-nation ideology that became prominent during that period saw some 28 French languages relegated to the position of patois or minority languages. The French revolutionaries were keen to ensure that all citizens shared a common language. Instead of considering bilingualism or a lingua franca—as is the case in the Philippines—they went about eliminating all competitors of French. This hostile policy towards minority languages was set out in Abbé Grégoire’s 1794 treatise entitled “Rapport sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser la langue française” (“Report on the necessity and means of annihilating the dialects and of making the French Language universal”).

This shows that minority languages are not necessarily the languages of a numerical minority. Rather they are languages that are subject to active processes of minoritization. While the term “minority language” suggests having small numbers of speakers, the term “minoritized language” is more accurate as it draws our attention to processes of language subordination and to the unequal power relationships that often pertain between “minority” and “majority”.

Clik here to view.

By contrast, citizens of the Philippines have many different mother tongues (Source: http://www.csun.edu/~lan56728/majorlanguages.htm)

In Europe, processes of linguistic suppression were so successful that by the second half of the 20th century most European nations were highly monolingual, with the vast majority of citizens speaking the national language as their sole mother tongue. However, globalization and migration of recent decades have thrown this high level of state-engineered monolingualism into disarray.

Many European states have reacted to this “linguistic threat” with new efforts at renationalization, as can be seen in the introduction of language testing for citizenship. Between 1998 and 2015, the number of European states requiring a language test from prospective citizens rose from 6 to 25.

Interestingly, this push to test the language proficiency of immigrants further helps to cement the minoritized position of indigenous minority languages: language testing in France, for instance, is done in French rather than in Basque, despite the fact that the latter is today recognized as an official regional minority language of France.

At the same time, globalization and migration have also pushed language ideologies in the opposite direction, contesting the monolingual one-nation-one-language ideology and giving new legitimacy to minoritized languages. Professor Amezaga showed striking evidence of this trend with TV signals: while around 1,000 TV signals from English-speaking countries reach non-English-speaking territories, 900 signals in languages other than English reach the US. The former is evidence that the media are agents of linguistic homogenization and the latter is evidence that the media are agents of linguistic diversification.

Professor Amezaga’s guest lecture focused on minoritized languages in Europe and the global North more generally. Reflecting on how these insights relate to my home country, the Philippines, it may seem that in this highly multilingual country processes of linguistic homogenization have not been an issue. However, that would be misleading. Our own version of the one-language-one-nation ideology could be called “two-languages-one-nation ideology”: English and Filipino are positioned side-by-side as an essential aspect of the bilingual identity of Filipinos. As a result, the Philippines’ other languages are similarly subject to minoritization.

Furthermore, the challenge posed by globalization and migration to the linguistic status quo of the Philippines does not come from immigration but emigration. Going overseas, primarily for work, has become a viable and even desirable option for many Filipinos, who perceive international labor opportunities as an economic panacea. Consequently, over 10 million Filipinos are estimated to be working or living overseas today. This number is nearly 300% more than the first wave of Filipino migrants in the 1970s, when the overseas employment program was launched. With Filipino migrants now gaining more ground as “workers of the world,” it is worth examining the language component of occupations where they are employed to see how their linguistic repertoire – borne out of a two-languages-one-nation ideology and differential valuing of minority languages – intersects with the language ideologies of destination societies.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Reference

Reference

The slides from Professor Amezaga’s lecture are available for download here.